When a Fandom Ruins Great Fashion

Prompt No. 28: Brand consciousness, White privilege, Taylor Swift Catching Strays, James

I own and routinely wear a few pieces that are recognizable to those with even a passing awareness of luxury, including Louis Vuitton, Cartier, and Tiffany & Co. Although these are tasteful, “reputably correct” staples made famous by a pantheon of stylish dead white women, my presentation is often summed up as “brand conscious”— a polite way of calling me a label whore. For the longest time, I felt pangs of embarrassment whenever someone made this point. To compensate for this misunderstanding, I exhausted accusers with my rationale. This is a connection to family, Black culture, and sometimes even private school. This is a complex love of fashion, not status emulation. Besides, if I wanted to signal anything, there are far easier ways than diligently tracking down long-forgotten discontinued items. After a while I noticed a trend: only white people felt the need to characterize my style in this way. Regardless of context or tone, my consumptive habits needed to sit in opposition to their feigned naiveté or contempt. Never mind their race serving as the ultimate signifier, allowing them to garner esteem — or simply the benefit of the doubt — without obvious indicators of cultivation. Expressing disinterest in fashion and luxury to a Black woman maintained not only class hierarchy but a racial one, as well.

According to W. David Marx, “status position is always contextual, based on how we are treated in a particular time and place,” a social reality Black Americans learned early. [1] Historically speaking, we have always utilized sartorial acculturation as a means of demanding fair and equal treatment in this country. Before attempting to escape enslavement, Black men and women made a point to steal garments to resemble their “free” brothers and sisters up North. Adoption of respectable, now considered “preppy” style sought to combat dehumanizing racist tropes, as Black protestors facing aggressive dogs, searing firehoses, and constabulary beatings were broadcast into American homes across the nation. Employing fashion far above our station as a means of garnering basic safety and respect has given us unique insight into the processes of thought and behavior that substantiate social hierarchies, even an understanding that something as simple as originality “may simply be the democratization of aristocratic custom.” By reinforcing one’s ability to move throughout society without the frivolity of fashion, those white people wielded a well-worn weapon of white supremacy, a bully club of a reminder that there are very clear limits to presentation, especially for Black folks.

That said, even with fashion theory and Black history on my side, I still feel a twinge of shame when it comes to my love of one luxury brand in particular. On the surface, Hermès feels a bit like the Taylor Swift of luxury; it’s unclear whether fans love it for the artistry or for what that art represents. Like Swift, Hermès symbolizes a highly specific white experience rooted in largely unattainable privilege, and as such maintains an outsized influence in American society. But as far as actual artistry, the parallels kind of end there. Hermès actively seeks evolution with real eras — the Margiela, Gautier, and Lemaire years marked by their unique perspectives on the storied house codes. For every overhyped classic like the Kelly or Birkin, there are truly interesting, lesser-known departures — the Initiale (the handles form the iconic “H”), the Opli, or the new Arçon. I would readily celebrate the French luxury design house, except — as in the case of Taylor Swift — Hermès fans suck.

Excuse me. nOt aLl hERMèS fans. Just Americans.

As a fundamental aspect of American culture, we all desire status as it plays an integral role in securing a comfortable social position. Both Swift and Hermès fandoms vehemently deny status playing any part in their esteem for the two brands, yet they center two of society’s strongest forms of exclusion: racial and economic privilege. In a 2007 article entitled, When White Women Cry, Mamta Motawni Accapadi explained:

“While White women have been depicted to be the foundation of purity, chastity, and virtue, Women of Color have historically been caricaturized by the negative stereotypes and the historical lower status position associated with their racial communities in American society. Additionally… ‘the problem for White women is that their privilege is based on accepting the image of goodness, which is powerlessness.’ This powerlessness informs the nature of White womanhood.”[2]

We do not need to cover the many instances where Swift, one of the world’s best-selling and subsequently most powerful musicians, positioned herself as a powerless victim. Suffice to say, her status is so intrinsically linked to this particular image that her overwhelmingly white female fans contort themselves to maintain it, fundamentally understanding (or in the case of her young fans, learning) that the very nature of their own privilege depends on it. Similarly, Hermès fans utilize affluence as virtue to maintain a false sense of exclusivity beyond the brand’s exorbitant prices. With roughly $10,000 in available credit, anyone can obtain a Kelly or Birkin secondhand. However, playing “the quota game” is the ultimate form of conspicuous consumption. It is not enough to simply purchase an expensive bag — the game demonstrates the ability to “confer special treatment and exclusive benefits” through wasteful consumption; quite literally throwing away money for the exclusive experience of being offered a more superior product. The problem is both fandoms seem to forget that others outside their communities must hold them in estimation to achieve status. However, when you strip away the pretense from both camps, all that’s left are a bunch of white women and girls clinging to nostalgia for their own self-preservation; not for acclamation or conservancy of art others might even understand, let alone desire.

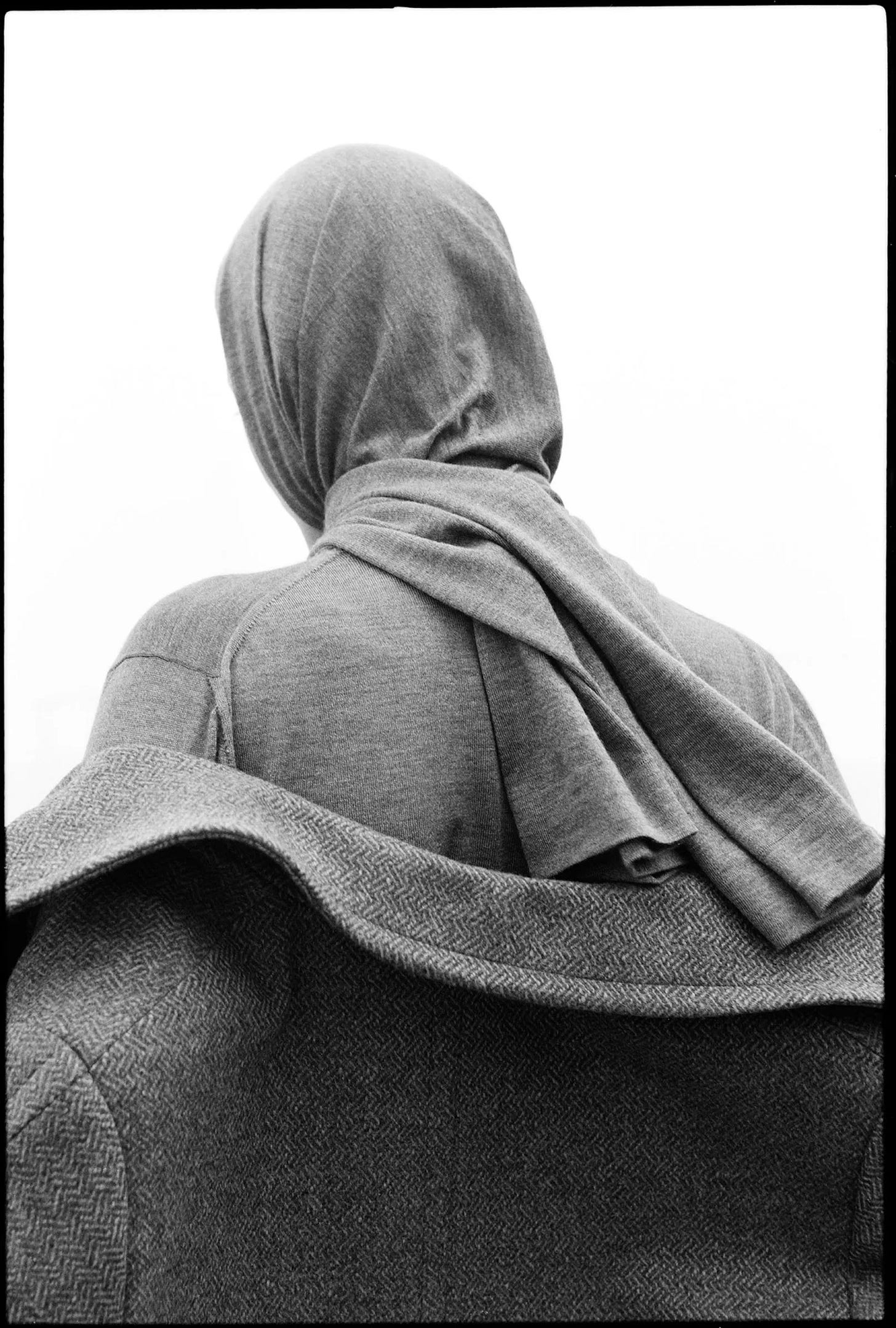

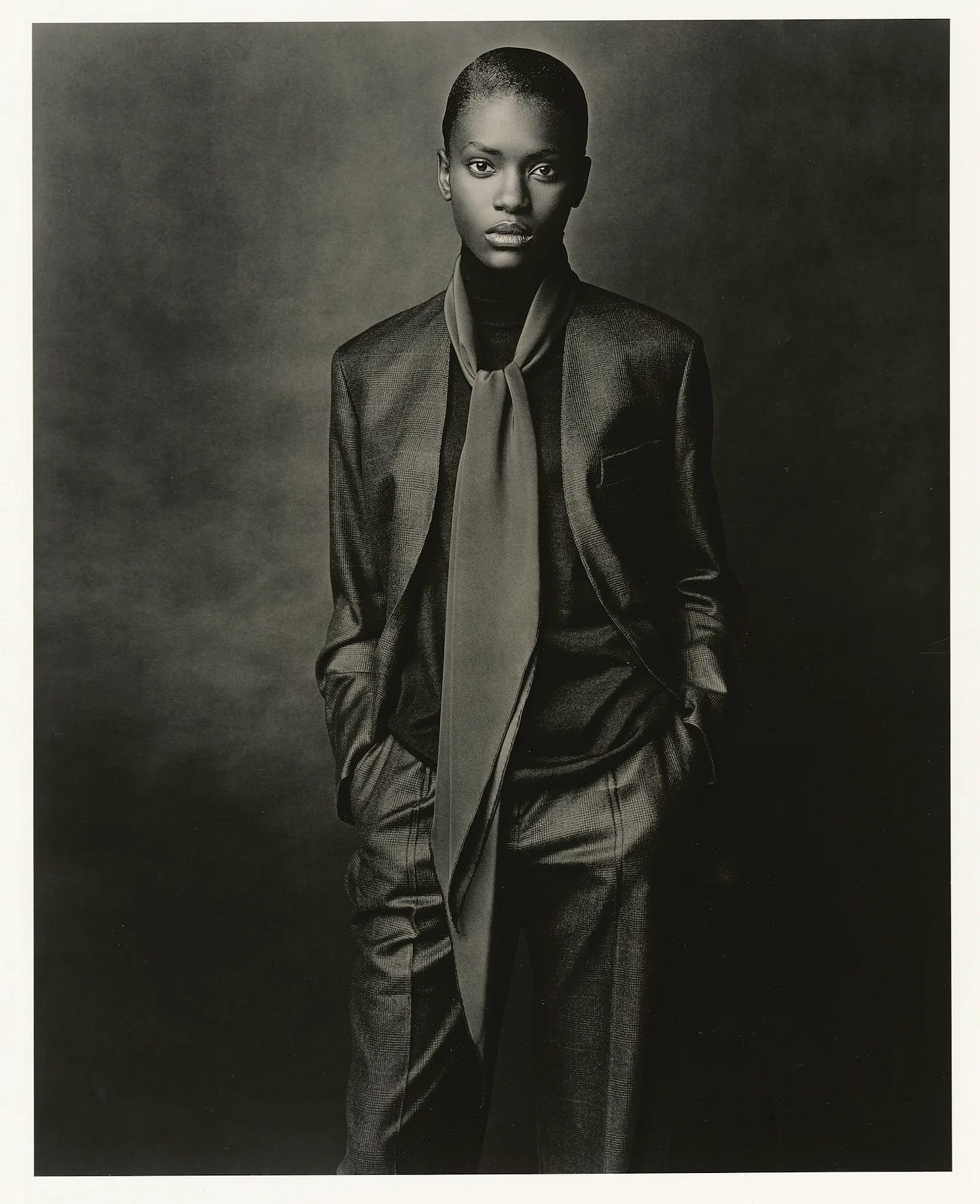

With that out of the way, I must confess I am still fighting the urge to explain why my love for Hermès differs; not simply to beat the label whore allegations (a Black woman could never!) but because I want everyone to see the true beauty of the design house beyond its most well-known items. In Martin Margiela: In His Own Words, the mysterious, avant-garde Belgian designer explained the tepid reaction for his debut collection for the house. Fashion editors, expecting some sort of absurd, deconstructed equestrian monstrosity clomping down the runway were perplexed by the restraint. The collection bore little resemblance to the daring Maison Margiela or the dowdy traditional look we associate with Hermès. It was in a word: perfection. I finished the documentary, mouth agape as if every sartorial prayer had been answered, then devoured every runway collection on YouTube. What I discovered was a design house committed to a timelessness tacked only as close to obvious signifiers as the customer wanted. Since, I have collected pieces from nearly all 14 product divisions, most for less than $500.

Now, if I can go largely undetected wearing one of the most conspicuous luxury brands am I still “brand conscious” or simply a Black woman with timeless style? I’ll wait…

[1] Culture and Status: How Our Desire for Social Rank Creates Taste, Identity, Art, Fashion, and Constant Change, W. David Marx.

[2] When White Women Cry: How White Women’s Tears Oppress Women of Color, Mamta Motawni Accapadi.

Orphaned Header: Initially, I thought a dedicated post on Hermès would revolve around Jane Birkin’s beat-to-hell bag; how many often attempt to replicate her treatment of the unfathomably expensive tote bearing her name, clasping all sorts of jangling shit to them in a devil-may-care insolence to conspicuous consumption. It’s weird and wildly imitative, but I understand the motivation; it is cheap hack to avoid looking tacky… by (arguably) looking tacky. But despite weeks of contemplation I concluded that is all I have to say on the matter. It became apparent there are far more interesting ways to tackle the complex role Hermès plays in America’s public imagination.

Acquisitions.

Here we acquire perspective, not just things and I wanted to create a playlist for this edition but all I can do is listen to Baby Rose. According to her bio, the artist is from both D.C. and one of the Carolinas (hopefully the good one with the only barbecue I acknowledge) so we can’t help but support off the strength of her roots alone. But if you need further proof of just how sick she is, check out her work with the incomparable Georgia Anne Muldrow on “Fight Club” and BADBADNOTGOOD on her latest single “One Last Dance.” You’re welcome.

As always, the double-asterisk (**) indicates a must-watch or read

Read.

Percival Everett Can’t Say What His Novels Mean (The New Yorker)**

I am so ready for James, a retelling of Mark Twain’s The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn. Now am brave enough to re-read the original in preparation like my dear friend Shelbey? Uhhh…

It’s Not High Fashion. It’s Upper Middle Class Fashion. And It Sells. (Wall Street Journal).

One of my favorite sweatshirts to steal from my significant other’s closet is a Todd Snyder x Champion sweatshirt. The man definitely knows what he’s doing.

It’s True: Back Pocket Denim Designs Are Making A Comeback (Vogue)

This is the only form of nostalgia I’ll accept. LONG LIVE 7 FOR ALL MANKIND! (But we can leave Balenciaga for all I care.)

Picasso Tried to Ruin His Ex’s Career. The Picasso Museum Will Show Her Art. (Washington Post)

If you do not know the story of Picasso and Françoise Gilot… No, if you didn’t know Picasso was a massive POS, read this.

Your Beloved Barbour Goes High Fashion (Grazia)

Bestill my heart. Doubt I can encourage my friends to send me one of these!

Okay, it’s late! Off to bed I go. Have a great week everyone!

Incredible piece! And I must agree the fans make it so boring. It was the Margiela documentary that made me interested in the brand beyond the bags, before that, if Hèrmes was mentioned I would roll my eyes. I have been reading more on its history and looking up collections, and other beautiful bags that they offer. A good brand.

I like Babyrose too!! Hauntingly beautiful voice.

Have a great week!

🥰